Using Toy Story To Understand The Kate Middleton Obsession and Backlash

aka the nuance of Buzz, Woody, and other cultural royalty

Two weeks ago, we began it wondering what was up with Kate Middleton.

We ended two weeks ago watching her somber revelation of a cancer diagnosis.

Interpreted one way, this is the natural order when fame and a mysterious crisis converge:

The larger culture notices something amiss with a famously famous person.

The consideration gestates to where the central amissness with the famously famous person reaches an almost total societal permeation.

This leads to revelations, which serve as a sort of punctuation to the whole affair.

This is mostly how it went with the Kate Middleton mystery, but I’m also reminded of the Tiger Woods incident from 2009. That entire affair began with a mysterious car wreck on Thanksgiving and then was slowly revealed to be related to his serial philanderings.

Interestingly though, with the Kate Middleton story, in the wake of our learning about her cancer diagnosis, there was a new step added to the natural order of when fame and a mysterious crisis converge:

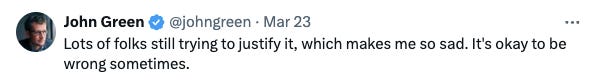

Reactionary moralizing happening from the vantage point of hindsight.

Anywhere you looked on the internet, people scrambled to “tsk tsk” how others interacted with the mystery, from group text threads to social media posts to national platforms.

At the Popcast, we did our own episode about the strangeness of the situation and then received our own flood of rebuke and scorn (some communicated tastefully, most though issued with vitriol and animosity).

If taken at face value, the vehemence of the disdaining was enough to convince me that maybe we all are disgusting and nosy little toads.

But the more I’ve thought about it, the more I wonder if the moralizing associated with our interest in a mystery may be misguided.

To be fair, I don’t think anyone is arguing that jokes or conspiracy discourse is fun when the final answer is “cancer.”1

But to be doubly fair, no one making the jokes or discoursing the discourse knew that cancer was the final destination on our journey of attempting understanding. They just knew something really strange was happening and the absence of any attempt at assuaging the strangeness was EVEN STRANGER.

This is the point that has vexed me the most. For all of us to be unified in our fascination over a mystery unfolding before us only to then be excoriated after the fact seems, at best, inconsistent and, at worst, morally performative.

We’d all JUST agreed that something was up. And for good reason! As a reminder…

The royal family, not exactly a paragon of truth and transparency, was obviously hiding something, which was later verified.

There were dueling PR teams almost willfully inflaming the mystery, which now looks even worse knowing the truth.

And the coup de grâce was a photoshopped picture the Royal family provided as a way to say, “Nothing to see here because things are so very cool and chill!” which was very quickly verified to be a bad photoshop job which had the effect of being confirmation chum to the conspiracy sharks.

Again, when the actual answer to a mystery isn’t conspiracy but rather an even worse c-word2, it applies a somber hindsight of perspective, making the discourse seem frivolous or reckless or in poor taste. And if those things were happening after the revelation, but they weren’t.

So I think this is about three things:

the slow death of nuance

the normalization of outrage

keeping perspective on the order of operations and our accountability to what we know, when we know it.

The first two are bigger conversations and, frankly, more boring essays, so let’s deal with the third item.

Specifically, let’s look at it through the lens of a scene from the iconic 1995 movie, Toy Story.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Binge Thinking to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.